I Used These 4 Systems to Figure Out My Personal Style

Personal style is probably more than answering the question “what do you like to wear?” but surely thinking through the inquiry gets close to the heart of it all. Personal style is about clothing our precious bodies in ways that make us feel comfortable, providing a sense of self in a colorful world, adding shading and texture to how we present ourselves to others, and signaling how we’re approaching the day. Said another way: personal style is what we like to wear, when we like to wear it.

Knowing what we enjoy putting on—and determining what we likely will enjoy putting on in the years to come—is the swath of the personal style puzzle that is largest, most oddly shaped, and most entertaining to piece together.

Since turning 30, I’ve been thinking much more about how I present the many facets of myself to the world. My 20s were spent purchasing clothing I liked. My 30s have been spent answering the question (largely without purchasing) of what I like, on the macro scale. What clothing feels right when I wear it? What are my dressing patterns, both now and over the last few decades?

Answering the larger, existential question of what I like (as opposed to the quick question of what I like, in a department store, on a singular Saturday afternoon) has been one of my life’s chief joys these last few years.

And beyond being a tasty, self-indulgent delight, answering the question of personal style has a dazzling side benefit: it’s probably one of the most sustainable things you can do in fashion. For one, it requires you to wear and play with the items you already own, which, according to a 2020 BBC report, is a great way to diminish the environmental impacts of your closet. For two, knowing what you like means you’re also knowing what you don’t like, so it’s probable you’ll buy fewer items that fast track to the landfill.

OK, I’ve made my case. Finding personal style is great. But where to start? Here are four frameworks I’ve used over the last decade.

#1: Outfit Tracking

I’ve said this before, but using an app like Indyx to track outfits every day is the single-best thing I’ve done to circle my personal style and reduce my compulsion to shop for stuff I probably won’t wear to death.

It’s valuable to be honest about what I actually put on my body—and to notice when and why I'm not wearing clothing that I ostensibly love. I don’t feel good when I wear tight shoulders and long skirts. I maybe wouldn’t have noticed that if it wasn’t super clear how little I’ve worn my fitted blazers and maxi dresses. When I’m looking at a calendar view of all the actual outfits I’ve worn, preferences and patterns become obvious.

Not only is it informative (and fun!) to create and re-use an outfit that feels amazing, it’s also liberating to articulate what I don’t like.

(For example, I rarely wear pants that risk touching the ground. I don't like clothes that are tight in the ribs or fit-and-flare silhouettes. I don't like high necklines. I do like open collars and untucked button-downs. I like cargo pants. I like things that are loose, with dropped shoulders and room in the thighs and knees for maximum movement. I like little touches that make me feel like a leading man in a period drama, crossing a meadow after a long afternoon outside.)

Creating a database of outfits I’ve actually worn has encouraged me to lean into certain silhouettes (big on top, big on bottom), fabrics (linens, cottons), and details (bishop sleeves, drape-y button-ups, halter tops). It’s also discouraged me from buying more of the items it’s become obvious I don’t wear (cap sleeves, most things in the color black).

Tracking my outfits also makes extremely clear what I wear in my real life versus what the daydream version of myself wears. Daydream Amy heads to an office on a cloud, with nothing in her bag but her journal and a secondhand novel. Actual Amy mostly works from home, stands on one-million-degree subway platforms, and hauls her 40-liter bag of roller derby gear the six blocks between the train station and the meeting location. Daydream Amy takes herself to solo dates at art museums and cocktail bars. Actual Amy is eating the same brunch every Sunday or playing a full-contact sport in basketball shorts and knee pads (fashion!). Daydream Amy wears denim shorts, socks with Birkenstocks, and flannels. Actual Amy… well, actual Amy does that, too.

And one last tactical advantage of tracking my clothing: I know what I have, so I’m less likely to buy duplicates. That’s not to say that avoiding a black blazer in your closet means you can never buy another black blazer, but it’s enriching to have a conversation with yourself about why you’re tempted by an item so similar to a piece you haven’t worn once in 7 months. (Maybe there’s a crucial fit or styling issue that this new item resolves, and it’s totally worth the purchase! Articulating that is a satisfying process, whether you buy an item or not.)

#2: Color Analysis

I think about this quote from early 20th-century humorist Robert Benchley often: “There are two classes of people in the world: those who constantly divide the world into two classes, and those who do not.” It’s not always valuable to put people in categories (to say the least), but it’s a natural human instinct that helps us make sense of the world around us.

Anyway, that’s why I like color analysis.

Much like hairbows, kitten heels, and straight-leg trousers, color analysis is an early ‘80s phenomenon experiencing a resurgence in popularity. It offers a framework for thinking through what colors “suit” you.

(An aside: a lot of style frameworks hang their value on what “flatters” or “objectively” “looks good.” That’s fraught and not the point of this article. It’s good to think of the conclusions from style frameworks as tools you can use or throw out. If you spend 10 minutes looking into color analysis, realize pink or another prevailing color in your wardrobe “doesn’t suit you,” and want to put this framework in the proverbial garbage—that’s amazing, excellent, lovely. Saying “I don’t care about color analysis because I love hot pink and will always wear hot pink” is a successful articulation of your personal style, which is the point.)

The essentials of color analysis are not complicated. The main assumption: people look good in colors with attributes that are similar to the natural coloring of their hair, skin, and eyes.

Colors can be assessed on three axes: temperature (warmth vs cool), value (light vs dark), and chroma (muted vs intense). Some articles describe the third axis as “contrast” or “softness.” If you can determine where you fall on these three axes, you can determine your “season” and thus what colors the system recommends for you.

Roughly:

Light and warm = spring

Dark and warm = autumn

Light and cool = summer

Dark and cool = winter

And then you can further subdivide the seasons by contrast. You can be a “bright spring” or a “soft autumn.” This article does a good job of getting into the weeds with it.

It’s a bit of fun—and I do find it quite helpful in helping me explain why some items don’t “feel right” when I wear them. I’m not about to avoid colors I love because they’re more “autumn” and I’m more “spring” (you can take mushroom-y green out of my cold, dead hands). But knowing my colors and leaning into them sort of works like an insurance policy, an extra bit of assurance that I will likely enjoy a new garment even after the trend tides shift.

I'm a spring (I think), and so when I'm looking for a sundress to wear to weddings this summer, I’m focusing on light blue, which I know will look good on me.

Color analysis has also set me free from pretending I like the colors black and gray, a conclusion that even on its own earns the system a recommendation from me.

#3: Kibbe Body Types

This one deserves a disclaimer at the top of the section: Kibbe really strays into the cult of “flattering.” If that’s not for you, go ahead and skip it. I put it in here because it has genuinely been helpful for me, and has provided me with some vocabulary about why some garments make me feel off-kilter and some make me feel effortlessly cool, composed, and (OK, yeah) good-looking. I’d recommend it if you’re someone who can eat the fruit and spit out the seeds.

Kibbe was my first foray into using a more methodical approach to finding clothes that "naturally" look “good” on me. This took my love for style quizzes in Seventeen and leveled up.

It's a highly detailed, not-scientific-yet-quite-exhaustive framework based on opposing, balancing forces shorthanded as yin and yang. (David Kibbe is a guy who grew up in Missouri and published this style schema in 1987. Take his interpretation of ancient Chinese philosophy with a Buick-sized grain of salt.)

I will avoid going into details about how to determine your body type according to Kibbe. There are long articles that do this quite well. Here’s one I recommend. And here is the video series that first explained it to me, which I initially watched because her voice helped me fall asleep.

Briefly: every body has a mix of “yin” and “yang.” Kibbe describes yin as soft, rounded, and short and yang as sharp, angular, and long. The way these features are combined in a person determines their Kibbe body type, and thus which sartorial choices (including clothing, haircut, and makeup) are “best” for them.

I like this because it has helped me describe my body in neutral, descriptive terms. It offers intellectual scaffolding that supports my opinions on what feels natural and what feels like performance.

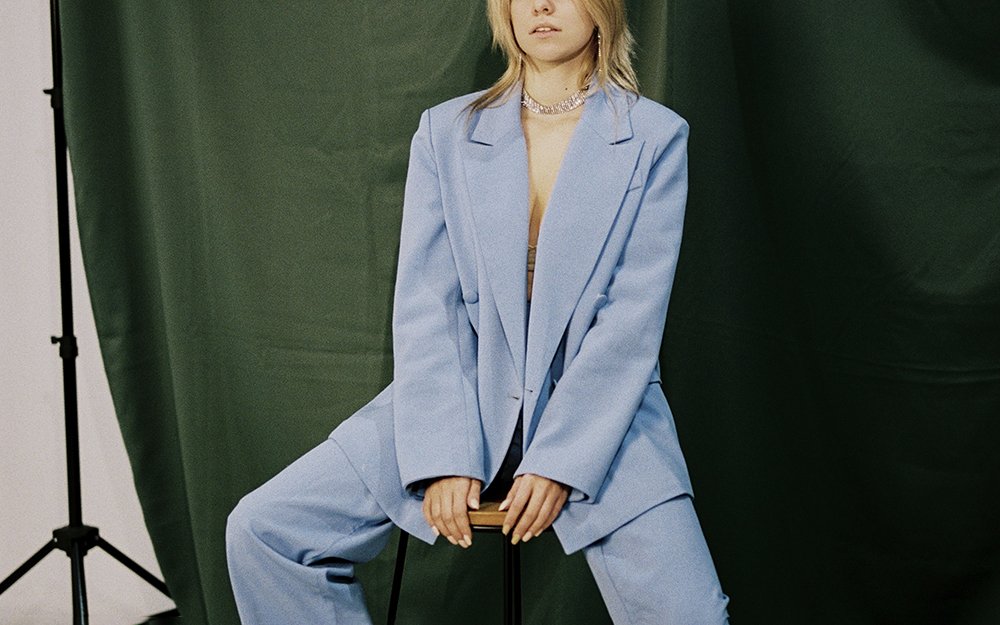

It’s because of Kibbe I finally let go of an expectation I would wear tailored clothing like crisp suits and waist-nipping silhouettes. Knowing what Kibbe says I look good in has empowered me to explore the same style words I’ve always enjoyed, but with softer, more supple pieces.

Honestly, in my usage of it, Kibbe is not really about style as much as it’s about shapes and materials. Most style words can be accommodated in any body type. You can be androgynous with a “romantic” body type, or edgy with a “classic” body type. It’s just giving you some more ways to think about clothing.

Suffice it to say: Kibbe offers a rich lore that is fun to explore.

#4: Minimalism

I can't stop thinking about Hannah Louise Poston's recent video on why she attempts to only wear two colors per outfit. I love it.

It’s a pretty simple guideline. First, choose your colors. Presumably this will be based on what’s already in your closet. With an app like Indyx, it’s pretty easy to see which 2 colors are your “dominant” colors, and which 1-3 additional colors are your “accent” colors.

See: my proclivity for white tops, which was easy to see on Indyx.

Second, as she says, “get comfortable with automatically not buying things if they don’t come in any of your colors.”

Third, wear only two colors per outfit.

That is (pretty much) it! I’m so excited by this. If you feel completely suffocated by not buying clothing in all colors of the rainbow, this isn’t your system. But I find it freeing.

After watching this video, I realized most of my clothing occupied a pretty limited palette of cream, mushroom-y green, brown, light blue, and navy. I have found it so satisfying to rule out entire garments because they are not available in my favorite colors. I have found it so much easier to look for a new work blouse or replacement sandals.

I recommend watching the whole video from Hannah:

Honorable Mentions…

There are more systems that people swear by. These don't really resonate with me, but they’re popular enough to deserve an honorable mention in case you find them helpful:

Three-word method — Describe your style in three adjectives, and use those words to guide you as you cultivate your closet. Allison Bornstein, the stylist who is often credited with recently popularizing this methodology, suggests choosing a mix of words that describes both what you wear most (you can better understand what you wear most by tracking your outfits!) and how you aspire to dress (often noted via Pinterest boards and influencers).

Feminine archetypes — These seven personas theoretically encapsulate the “essence” of feminine people. The ideals include the Mother, the Maiden, the Huntress, the Queen, the Sage, etc. I love storytelling taxonomies and Dungeons and Dragons and categorization frameworks, but for some reason this one feels too reductionist for me.

Capsule wardrobe systems — Project 333 is probably the most popular framework right now. In essence: every three months pull out 33 items (including accessories and jewelry!) to wear exclusively during that season. It forces you to think through what you want to wear roughly once a quarter as well as reduces decision fatigue once the plan is in place.

Learn more about our (free!) 8-week course that guides you through a step-by-step process to get inspired, define your style, and create a plan to build a lasting wardrobe to match.

Amy is a writer and product manager with twin interests in beautiful things and trash. She plays roller derby and otherwise enjoys historical fiction and Diet Coke.